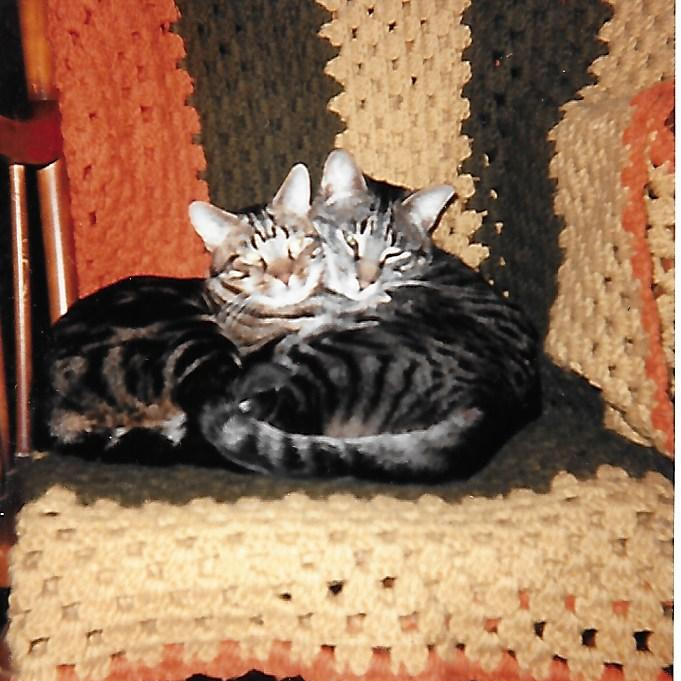

This year, 2025, marks twenty years since I was back on the road with Tundra, driving from my new Cape Breton home to Calgary and back again. I’d already done that road trip five times, so I was an old hand at long days on the road, finding free overnight stops, and the best backroads. My first big cross-country trip was in 2001, when I spent a year on the road with Tundra. We visited all ten provinces and Yukon territory, but Cape Breton captured my heart.

I moved to Cape Breton in 2004, with my travel trailer in tow and Tundra riding shotgun, as described in Twenty Years in the Holler. But I still had one foot – and a house – in Alberta. It was time to head back to wrap up loose ends and cut ties with my home province. I had a house to empty out and sell up, and family and friends to visit. So in August of 2005 I drove back to Alberta, Tundra by my side, to complete the relocation from Calgary to Cape Breton.

I’d rented my Calgary house out in 2001, the year of the big road trip. Now my tenants had given notice and it seemed best to just sell up. But first I had to empty the place out. Most of the furniture had to go, and my son and I had to sort through piles of stuff we’d accumulated over the years.

It just so happened that my son and his partner were renting a place three doors down, so we had a fun summer being neighbours. I could walk over in my slippers to enjoy a BBQ on their balcony; my son could drop Tundra off on his way to work. Meanwhile, we picked away at the pile of stuff. It was a bit of a job, with a lot of memories to sort through.

My son donated his stash of childhood action figures to charity. Who knew they would turn into valuable collectors’ items? But it also turns out there’s a whole lot of stuff you can’t give away – no one wants it. In the end, I had to hire a one-ton truck to haul a load of rubbish to the dump, which deeply pained my frugal soul.

Speaking of frugal, I decided to try selling the house online myself to save thousands in real-estate agent fees. It was a small bungalow, built on a hillside above the Bow River with lots of privacy and a lovely view out back. But the front was below street level and totally lacked curb appeal. I was standing on the road taking a photo when a man pulled up beside me and rolled down his window. Hippie guy, long dark ponytail and beard.

“Hi. Do you know of any houses for sale in this area?” Seriously?

“… Uh … yeah. This one,” I replied.

He and his wife were teachers in the Yukon but were moving to Calgary in a year. He was on a quick trip to buy them a house before prices went up (same reason my tenants had given notice – they bought a house). He liked Montgomery, an old neighbourhood nestled into a meander of the Bow River, so he’d been driving around looking for ‘For Sale’ signs when he happened upon me standing in the road with my camera. What are the odds?

He came inside, took a look around, and asked, ‘How much do you really want for it?’ I liked him, this long-haired teacher from the Yukon, and I opted to be upfront. I named the price I had decided as my bottom price, one that was reasonable at the time. He agreed. I called the lawyer who’d done the paperwork when I bought the house. It was late Friday afternoon, but his office was nearby and he agreed to see us. We scooted over and signed the paperwork. I paid the lawyer and the deal was done – just like that.

And what a deal! Both the buyer and my tenants were a whole lot more savvy than me. Calgary house prices went through the roof the following year and kept on skyrocketing. That little bungalow had almost doubled in price two years after I sold it. C’est la vie.

Possession date loomed and I was under the gun to finish purging and packing. I bought a 6’x12′ cargo trailer to haul and store items that made the final cut: tools, camping gear, art work, art supplies, musical instruments, bags of clothes and bins of books, and my beloved rocking chair. I filled the cargo trailer to the roof and piled rubber totes into the truck bed, strapping my trusty bicycle on top. And then I bungeed Spot in.

Spot? A very original name for the big stuffed dalmatian that my mum won at the Stampede and gave to my brother and me when we were children. He was life-sized and I adored him. Dolls? Meh, not my thing. But I loved Spot and all my other stuffies. To me they were alive, my beloved friends and playmates. And there I was, 49 years old, and faced with letting them go. Too old and grubby to donate, too precious to trash.

Right: Mum with my brother and I – all duded up for Stampede. Pinky is in the crook of my arm.

I picked the oldest and dearest and packed them in the cargo trailer, but Spot rode where all dogs used to ride, in the back of my pickup truck. Tundra lounged in the lap of luxury, on the bench seat beside me.

I left Calgary on September 9th, 2005, four years and one day after I left on my epic 2001 trip. As always, I lined up Truckin’ by the Grateful Dead on the tape deck, and, as always, I took the prairie backroads, which, according to my journal, varied between ‘the good, the bad, and the ugly.‘ It was getting dark when I stopped in some small prairie town for ice. I’d just passed an older fellow with a long white beard on a bicycle, and now he passed me and called out, “I like your dog!” “Thanks!” I called back, confused. Tundra was curled up on the passenger seat – no way he could have seen her. Then I realized he meant Spot. Cool.

We rode out a wicked scary thunderstorm overnight in the Qu’Appelle Valley in Saskatchewan. The next day I had to pull over when we hit a black wall of rain so thick I couldn’t see a thing. It finally cleared and I stopped at a little cafe in a small town, well off the beaten track. All the regular fellas sitting at the formica counter turned to stare. I ordered a grilled cheese sandwich and the guy behind the counter got it started on the grill. Then he leaned back and looked at me.

“So what the hell are you doing in Punnichy anyhow?” he asked.

I laughed. Good question.

“Driving to Nova Scotia,” I replied. I mean, why else would I be driving along some lonely gravel road 120 kms north of the TransCanada Highway? I guess they don’t get a lot of strangers in Punnichy. And that’s what I love about taking the backroads.

The other great thing about the prairies are the skyscapes. Land of Living Skies is an apt license plate for Saskatchewan and is true of all the prairies. But the most stunning skyscape happened on the second night of our journey east, just past Winnipeg. I’ve seen the northern lights quite a few times, but nothing like these. I found a turnout and pulled over. Here’s what my journal has to say about what happened after I stepped out of my truck.

Aaaaahhh! I scream – in surprise and delight and astonishment at the heavenly dance overhead. Then – aaahhh! – red and blue and white shards of light splinter dance swirl – I am in a magic world both ecstatic and a bit frightening in its intensity, its beauty. It’s awesome – in the the true sense.

True awe. It’s not just a sense of wonder, but wonder tinged with fear, with a feeling of being overwhelmed. Of being very tiny in the vastness of the universe. I can understand why indigenous people have a spiritual connection to the aurora borealis. It’s so much more than a celestial light show.

We spent the night in the parking lot of the Welcome Centre at the Manitoba/Ontario border. The next day I drove off to the music of Little Feat, feeling infused with spectral energy. When I stopped for gas, a woman came up to the pumps, laughing. I’d forgotten about Spot.

People warned me, the first time I set off to drive across the country, that I would spent half my trip driving though Ontario. They weren’t wrong. Unlike the east/west roads of the prairies, there is a lot of driving northeast then southeast, rounding the Great Lakes. Every sign says the next city is 600 kms away. It’s beautiful country around Lake Superior, but on this trip the skies were hazy all the way. Plus it was much too hot for September.

Sault Ste. Marie is the half-way point between Calgary and Cape Breton. I called my son from a pay phone and greeted him by saying, “This is Sue, calling from the Soo.” After a nice chat I kept on driving. And driving. There were way too many big trucks after dark so I opted to stop for the night. My journal laments the unseasonable warmth.

“I duck into a picnic spot and try to sleep in the godawful heat – sweating in the stuffy back seat – no breeze – in mid Sept!! I hate Ont., I’m thinking as I lay there. Finally, 3ish, I sleep until 8ish then up and off in the haze and it’s warm already.”

Well. So much for the joys of being on the road again. It ain’t all roses.

My favourite road song is ‘Truckin’ by the Grateful Dead. I think of the chorus as a refection on life, but on this road trip these lyrics were literally true.

Sometimes the light’s all shinin’ on me …

Other times I can barely see …

Lately it occurs to me –

What a long, strange trip it’s been.

If Ontario was long (and hot and hazy), Montreal was terrifying. I hear there’s a ring road now – not to mention GPS if one has a smart phone – but back then I was driving a big pickup and hauling a trailer while trying to navigate roads and construction detours, surrounded on all sides by insane Quebecois driving as if they’re racing in the Grand Prix. No matter my careful plans, my attempts to memorize the simplest route, it was always a nightmare and 2005 was no exception. I decided to go at night – less traffic. It turns out that’s when they do even more construction so it was ALL detours. I got totally lost and discombobulated. Arghhh!

But somehow we made it through intact and I pulled into the first rest stop. I’d never see one so crammed with big rigs. I figured they all went through Montreal at night and then rested. I slept in the back seat, relieved to have the worst behind me. The next day we took a peaceful road that parallels the highway along the St. Lawrence. We stopped in the beautiful village of Kamouraska, made famous by the Quebec writer Anne Hebert.

I turned off at Riviere du Loup, saving the rest of the Gaspe for another day. Then across country to New Brunswick. Six days on the road and we’re finally in the Maritimes – ‘yahoo!‘ my journal says. But it still wasn’t a cakewalk. I ended up driving at night, worrying about bright headlights and dumb moose, then almost ran out of gas and had a hard time finding an all-night gas station. Near Fredericton I forked out $65 for the luxury of a good night’s sleep in a motel.

After all that heat and haze in central Canada it was wet and rainy in the Maritimes. We scooted through New Brunswick and made it to Nova Scotia. That got an all-caps YAHOO! in my journal. Had to stop for the obligatory photo at the lighthouse sign to add to my collection from previous trips. It was ‘very cold and windy‘ and I got my photo and got back into the truck just as the heavy rain started. Spot got soaked, but at least he didn’t get that wet dog smell.

It was dark when I crossed the Canso Causeway and I wanted to arrive back in the Holler in the daylight. So I splurged on another night in a motel. My journal has a page of complaints about the woman who tried to overcharge me the next morning and spoiled my happy Cape Breton vibe. But now, twenty years later, I’m over it. In fact, I’d forgotten all about it, so I’ll spare you the details.

I drove past the beautiful Bras D’Or Lakes, blue under a blue sky, and my angry frown flipped into a smile. Stopped at the Gaelic College CAP site to check emails and visited the William Rogers art gallery, then around the loop, “lovely and me happy and feeling good.” Stopped at Piper’s campground for ice (the CAP site, the art gallery, and Piper’s are all gone now). And then … home to the Holler.

I unlocked the gate and “All is well, gate in place, no fires in the firepit since mine, everything is just as I left it.” I pulled into a turnaround to park and unhook the cargo trailer, then went across to the neighbours’, where I’d left my travel trailer, and received a warm welcome. I hooked up my travel trailer, hauled it back, got it turned around and maneuvered into place and unhitched it from the truck. “Roadeo is free again!” I wrote.

I was all set up and ready for the remnants of Hurricane Ophelia to welcome me home. “I felt so happy and content to be home,” my journal says. “Gotta get used to saying that – home.” It’s been twenty years since I wrote that. And I am still ‘happy and content’ and very used to calling Highland Holler home.

Sue McKay Miller

December 28, 2025